Mostly a short methodological note

Budgets and Prices

There has been a lot of discourse about “shock therapy” since the 90s and it got revitalized by a new book How China Escaped Shock Therapy recently. It’s one of the few situations in which I think that the discourse on the topic is completely incompetent on some basic level because participants don’t really understand the underlying mechanisms and facts about underlying economies and it happens only on the level of rhetorics or other amusing History of Thought.

The first point is a simple idea of the economic theory when you speak about prices and try to postulate their effects, you shall never speak about prices alone because prices are meaningless by themselves, they have an effect on the world only by the way they interact with budgets given the preferences. For some mysterious reasons, they never exist in the public discourse related to shock therapy together. You can read substacks about price theory.

We established that we should look at budgets. What was the situation with budgets in the socialist states going into the transition? As it was a socialist economy, two points about the structure of the budget exist.

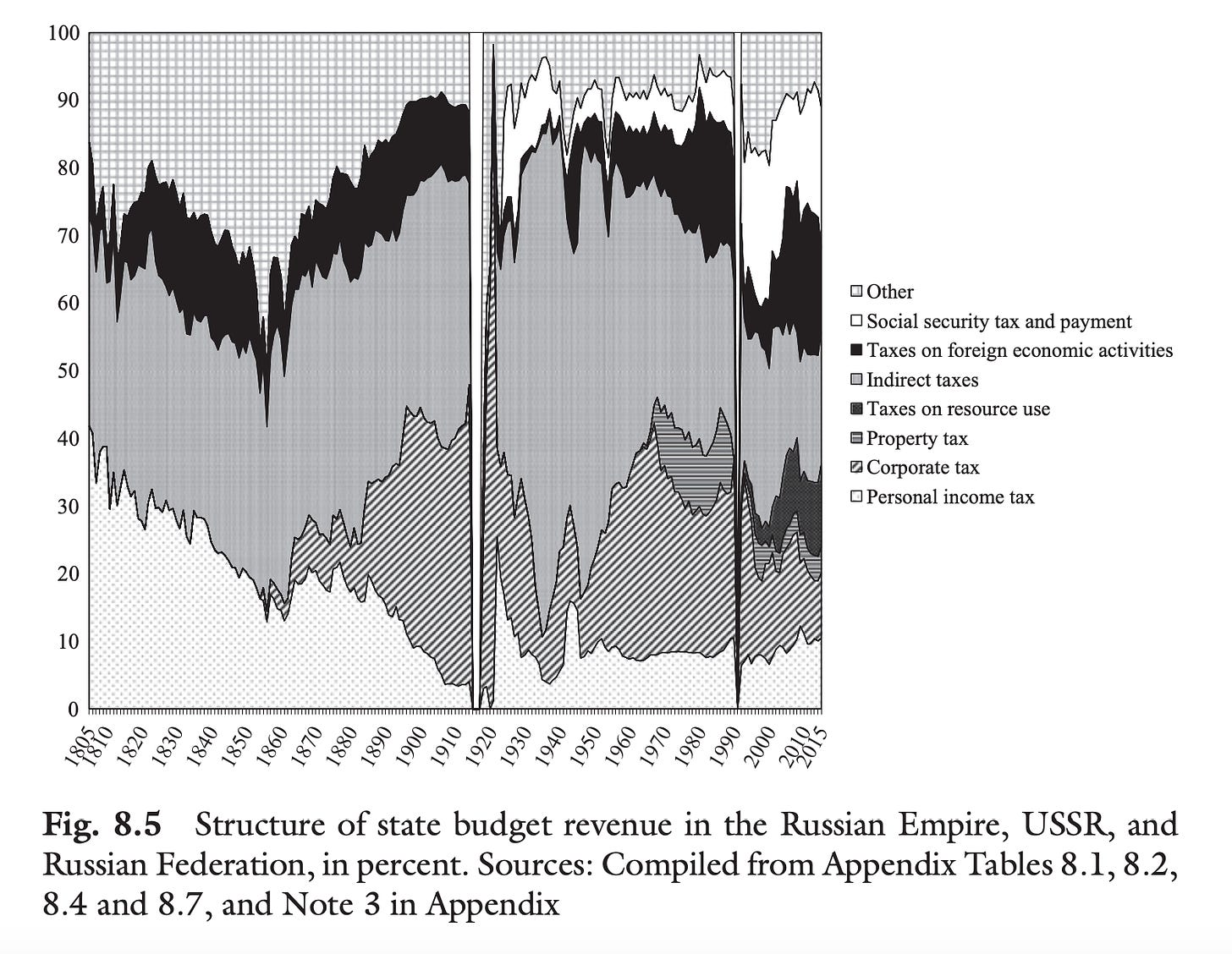

A less relevant for the operation of socialism, but important for the transition point is that it was a corporatist economy, a major social and economic unit was the corporation, and hence the major unit of tax collection was a corporation. The government collected the majority of its taxes through the taxes on enterprises and their foreign economic operations and not from personal taxes as in a large share of liberal democracies.

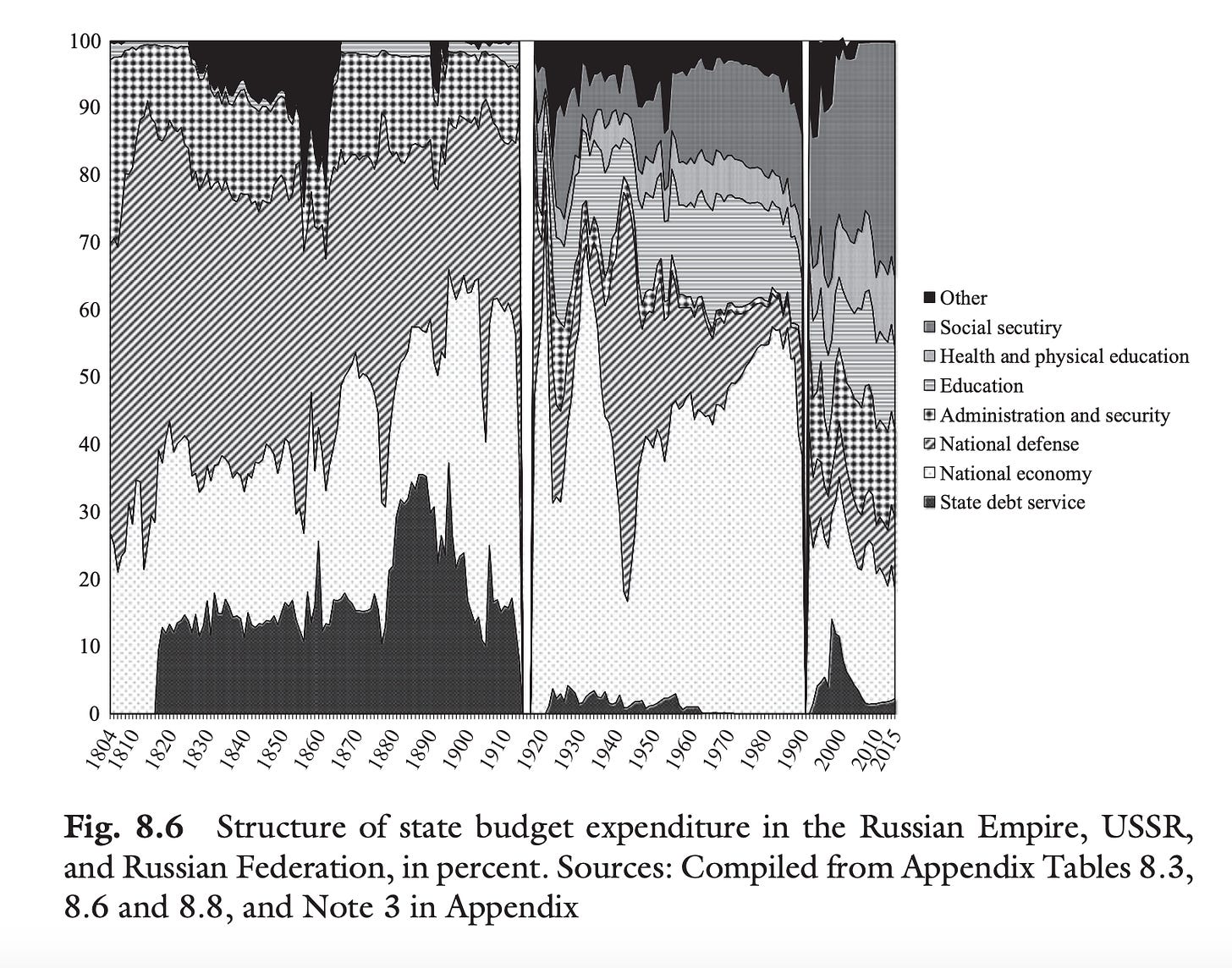

As it was a socialized economy, a noticeable share of enterprises was actually losing money and increasingly so with time (it’s really ironic in the context of the endless discourse about the greater role of profit and reconstruction of capitalism) and for their operation, they needed to be subsidized which was eating an increasing share of the budget (in the Soviet budgets designated as “national economy”).

How is it connected to “price controls”? We can start with an idea about how capitalist firms are operating: they are producing goods using goods, labor, and materials that are supplied to them for money. If they make profits, they can continue their operations, if they don’t make profits, they either close or need to find a source of external financing. The socialist firms are different in the institutional details of how they work in everyday operations, but the most important part is that they are rarely closed and that they have far larger and almost endless access to external financing. This idea creates the largest misunderstanding on the topic: a firm not needing to balance a budget doesn’t really mean that the state doesn’t need to balance it in some capacity, the nasty effects of increasing monetary pressure still exist, you just kicked a can down the road to someone else in the economy.

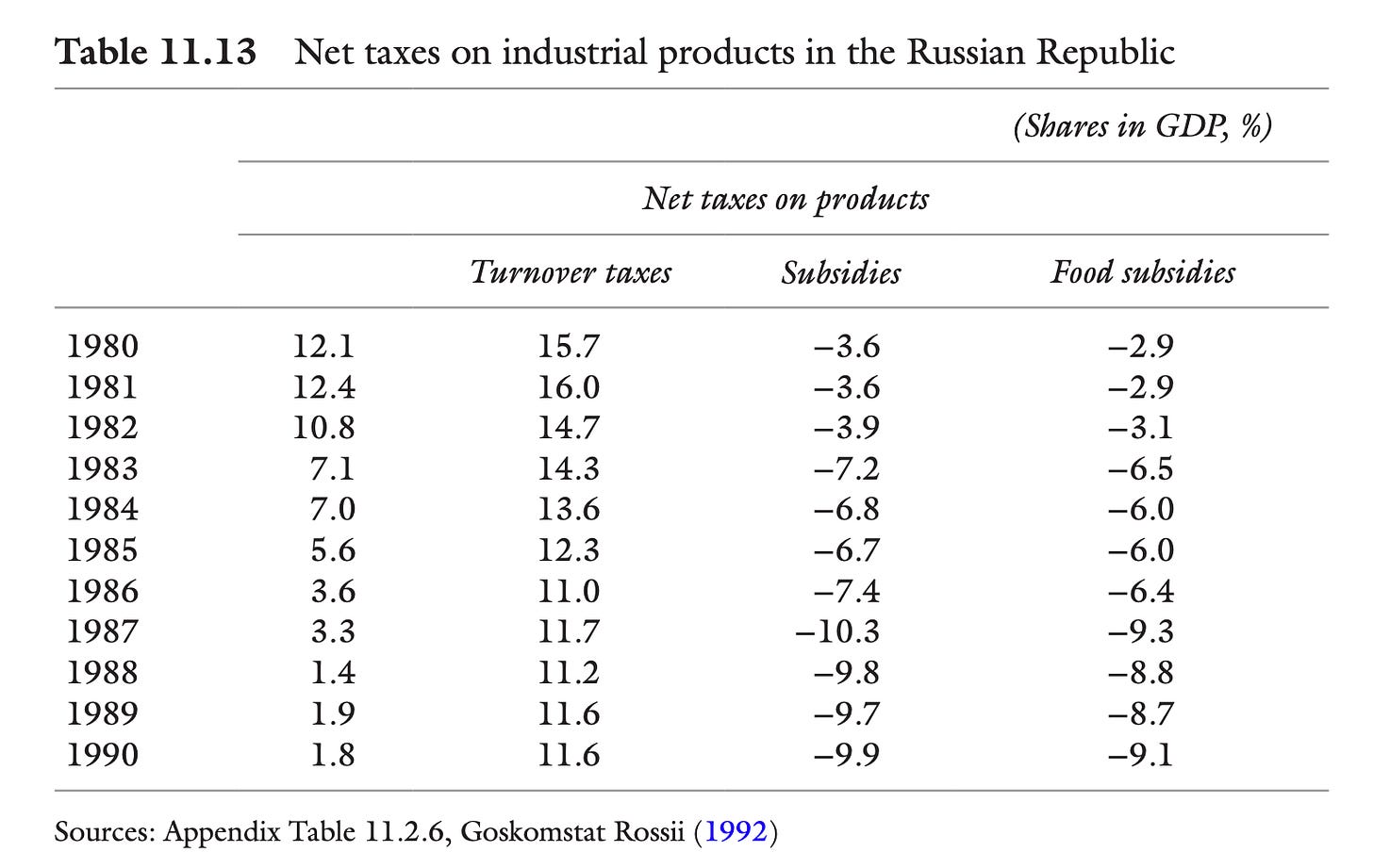

Normally, we can postulate that some natural prices exist, ie prices that will be established if the price controls will be lifted (it does make sense in some situations, but not always). In our situation with the socialist economy, we can think about the situation with fewer assumptions in which firms face one set of costs/prices and then sell things with the other set of prices. We can set them higher or we can set them lower. In some situations, especially related to consumer-facing items, we may want to set prices lower than the producer costs. This will necessarily mean that firms will earn less money and we can push them to stop being self-financing and hence needing external subsidies.

https://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/download?doi=10.1.1.472.3357&rep=rep1&type=pdf

A large share of the late socialist states ended in a situation of

Massive and increasing subsidies are needed to sustain their economy and consumption patterns

Rapidly escalating deficits

Moderately escalating inflation (which was a historical reason that had a far more corrosive political effect, it’s not Argentina)

The idea that one can have surviving price controls should necessary be paired with “how would you pay for them” too, as most things should, at least in the sense of how you can sustain general fiscal control on the aggregate level and production networks as such.

Trade

None of the socialist states existed in a vacuum. And some of them were in the process of disintegration, hence the entire exercise of price controls and saving production networks demanded cooperation because, surprisingly, you can’t price control things in other countries, you once again can only cover the differences, but now it’s even harder because it needs you to get your hands on foreign currency somehow.

Socialist states traded with each other and the outside world. They traded with each other on fixed administered prices in transferable rubles (which like most good things exemplified by HRE, were neither rubles nor transferable) which led to the situation of the socialist trade being a quite peculiar enterprise, but in the end, COMECON was abolished, the trade between ex-members was done in a quite complicated mix of local currencies (including a short-lived ruble zone) and dollars from now on. If you are in Russia, you can’t price control Ikarus buses in Hungary and people in Hungary will be buying your stuff for real money from now on too!

The same argument exists for the disintegration Soviet Union in a similar manner. It can be surprising, especially in our day and age, but the Soviet Union and Russia are different countries. At the moment of shock therapy, close to 50% of the Soviet population and a decent size of its economy were in a different country. The government in Moscow can’t set prices on goods produced in Kharkiv if they are in a different country, in a similar manner, the government in Kyiv can’t control the prices in Mogilev. Such is a way of national liberation.

Production networks

There is an argument about how price controls should have been maintained to maintain the current production network and make the transition smoother. I think it’s a coherent argument on a face value, but people need to make it explicit, but once again, you need to have the idea that you are propping firms that can’t self-finance in it still and you need a way to fund this exercise and there is no reason to actually assume that it will end well from current empirics or abstract theory.

Real austerity has never been tried

Russia ended in the worse possible of worlds in some sense: the prices were freed while the government didn’t try to introduce relevant laws and actions for fiscal correction almost at all for several years: there were persistent deficits and a lack of almost any needed institutions until 1995 (one can note the new law on Central Bank, from April of 1995 as a turning point)

CBR continued to give credit to ex-Republics of the Soviet Union

CBR allocated loans to enterprises in an administrative manner with negative real interest rates (which made both microeconomic and macroeconomic correction worse)

CBR directly financed deficits through seigniorage in the first years

(2) can be viewed as a peak of social dysfunction and depravity in this situation. You privatize assets in an unfair manner and create an unequal society, but you also sabotage both declared goals of the privatization: macroeconomic adjustment because you continue to spend money to prop enterprises and microeconomic adjustment because you are paying them to not change their operations as fast as possible.

Social spending declined, but it’s far more simple and less nefarious than people present: from a nominal side, tax collection declined by a massive amount due to differences in the state and economy during the transition and general weakening of the state, and from the real side, the economy was in a 10-year-long recession until 2000 with both growth beginning and inflation receding by 2000.

The relevant adjustment wasn’t done during the Yeltsin era greatly because the large adjustments are politically hard (once again, the Soviets were afraid to rise prices for decades for purely political reasons). Yeltsin’s government increasingly lacked a political mandate, it’s a quite simple and direct idea, if you can’t understand, it mostly tells bad things about you in the first place, as exemplified by a popular History of Thought person Slobodian here.

The source of the graphs is Russian Economic Development over Three Centuries.